Property of National Association Rainbow Division Veterans

3-4-006

Copy #1

From Library of John D. Brenner

This book is reverently dedicated to the memory of the members of the Rainbow's Sanitary Train, who will not come home.

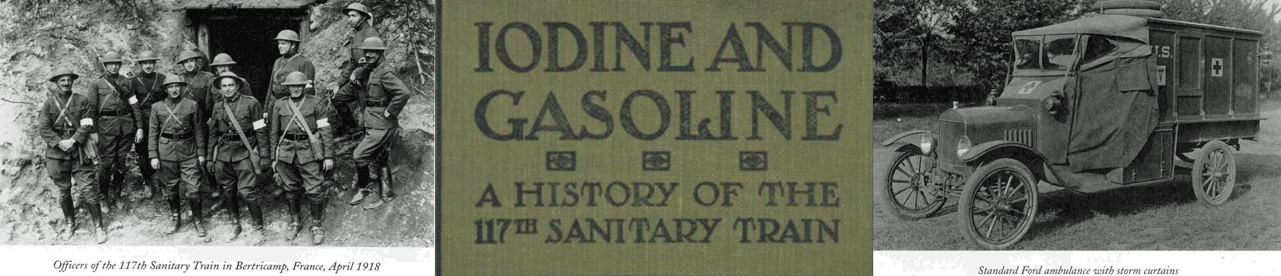

No words that I am capable of writing can add to the splendid reputation of the 117th Sanitary Train. Let the mute testimony of the shell-shattered ambulances and shell-destroyed hospital of Champagne be made of record. The watchword of the Field Hospital Section was "Instant Service," and no dangers restrained the Ambulance Section from pushing its ambulance-heads to where it could render immediate aid.

The record of 22,260 patients evacuated from the firing line during action by the 117th Sanitary Train is a record of which every officer and man of the organization may justly be proud. So many old members of the train, standing in ranks with wound chevrons at the last review of the Division, was the finest possible testimonial of work well done by you.

W. N. Hughes, Jr., Colonel, General Staff Corps, Chief of Staff, 42nd Division.

The train was composed of eight companies from as many states. The staff consisted of enlisted men of all Medical Department ranks permissable in a sanitary train, 18 in number. The staff was selected by finding two alleged writers in each organization, choosing two others at large, and detailing them to write. The necessary authority and money was supplied by Lieutenant Colonel Wilbur S. Conkling, the commanding officer of the train.

The purpose of the book is to refresh the memories of the members of the train in after years, and to bring such pleasures as the memories may— "Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit." In short, it is written by, for, and of, the enlisted men of the 117th Sanitary Train of the 42nd Division. Other people are invited, but not especially urged, to pour over its contents, because it might have no special interest to persons having no friends in the organization or not being otherwise concerned in the workings of a medical organization of a combat division.

The information herein was obtained from company records which were kindly placed at the staff's disposal, from diaries of friends, and personal memories. It is with genuine pleasure that the staff offers this book to the Sanitary Train, sincerely hoping that it pleases.

But the tale of how dough-boys of the division began to watch for their sign in the heavens, and how it really became to them the "bow of promise" on the battlefields of France is a story which is not so well known. That, like all traditions, grew. It grew behind that curtain of censorship which kept the enemy unadvised of the torrent of men and munitions America was speeding into France, and behind that curtain which likewise kept fond hearts at home from knowing just all that their boys were doing to free the world from a hateful system.

As has been said, all traditions must grow, but likewise all traditions must have a beginning.

Perhaps no spring has been more dreaded or awaited with more breathless expectancy than the spring of 1918. All through the longest and most severe winter of the war ominous† "omnious" [sic] threats regarding the greatness of the storm that spring would bring had been filtering out of Germany into France, England and America. The vast Teutonic propaganda octopus was spouting ink from a thousand mouths. All sorts of rumors were afloat concerning the greatest of all offensives with which Germany hoped to finally crush all resistance of the Allied powers. Whispers were heard here and there of a new and irresistible† "irressistible" [sic] gas that would kill all before it. Insidious† "Insiduous" [sic] tales were passed by word of mouth with the rapidity of lightning, apparently reaching all parts of the world simultaneously. Dame rumor was never less idle.

So the spring was dreaded because of new horrors it held in store. It was waited for because the Americans would be there in force to put their shoulders to the wheel and to lighten the grievous burden. It was hoped for because it would bring relief from the suffering of winter trench warfare.

When warm showers and bright sunshine began to replace the blighting cold and rain and 1eaden skies, when warm breezes once more wafted downy white breakers across the blue sea of heaven and gently awoke the world, they found the 42nd American Division holding a sector in the Vosges mountains, but a few hundred yards from the border of France's lost Lorraine. The Division had been there since mid-winter, and war seemed to be a drab sort of catastrophe as viewed from these thinly held mountains with their occasional raids and minor battles, but continuous mud, snow and rain.

It was whispered about that an attack was to be made, as is always the case no matter how much secrecy is observed in preparations for the action. Those who were in support saw long, dim, creaking lines of artillery and ammunition come stealthily up the roads under cover of night and disappear before morning under natural and artificial camouflage. Before many days had passed every clump of trees in the rear area of the sector was bristling with guns and shells and men all waiting. Finally the day came and at the appointed hour all the masked guns leapt into action. For hours the air was filled with screeching† "screaching" [sic] steel. The earth trembled at the continued explosions that scratched and tore at its face with venomous† "venemous" [sic] claws.

With dawn there came the promise of a smiling sun after the drizzle of the long thunderous night. And with it "H" hour. Out of their crumbling sloppy trenches clambered the doughboys at the signal. They moved forward through openings in the tangled masses of barbed-wire and spread out behind the awesome curtain of the creeping barrage.

Suddenly one of the bent-over, intent, jogging figures looked up and ahead and saw that the first rays of the rising sun had painted a rainbow across the receding clouds. "Look!" he shouted to his neighbor runner and somehow getting his attention above all the crash of artillery and sharp sputter of machine guns pointed to what he had seen.

Odd as it may seem that such a commonplace thing as a rainbow would draw attention in the midst of such stern business, the word passed up and down the line of crouching runners and all took a moment to look. But the first line trench of the enemy was at hand. After a few moments of brisk hand-to-hand fight-

Back again in their own trenches the story of the rainbow leading the attack was passed around. Before the end of the day it had been told and retold to every man in the Division.

Spring had merged into summer. The mightiest effort of the Hun hordes was stemmed and the flood began to recede, slowly at first and then more and more quickly as confidence waned and the lines were thinned by the storms of steel. One day in late July the Rainbow Division was struggling through the Foret de Fere north of Chateau Thierry and near that little stream, the Ourcq, which has written itself ineffaceably in the history of America. For days it had been fighting against tremendous odds in those tangled woods and across those golden and red fields of wheat and poppies. By wild charge, by stealthy advance it had captured nests of machine gunners entrenched, or perched in trees. Against two "invincible" Prussian Guard divisions it had steadily advanced to the foot of Hill 212.

Here was the deadlock. Backward and forward the lines swayed as a height was taken or a village captured, lost and won again within the space of a few hours. Hill 212 was a strategic point and must be taken before the troops could advance and wipe out the threatening salient. Artillery was brought up and the attack planned. The hour came. As the tired waves of men began their leaping, falling, crawling, halting advance towards the crest, an astonishing phenomenon appeared. Clouds that had soaked the earth during the night parted, and across the wooded crest of the hill was brilliantly etched the Bow of Promise. It was a promise of Victory. The fighters forgot their fatigue horror and hardships of the past weeks. With a wild cheer they burst into a fierce charge. "The Rainbow! The Rainbow!" they shouted, and again the familiar "Heaven, Hell or Hoboken before Christmas." All waves swept on and up in the face of showers of bullets and shrapnel† "schrapnel" [sic], and they captured the heights without faltering. And again the story was told of how the battle-sky had held aloft the emblem of victory.

In September the division moved up from a short rest to the "Sector northwest of Toul" by forced night marches. In a steady downpour of rain the troops splashed into the trenches on the

With the break of day, "H" hour struck and the First American Army began its first independent offensive. Its purpose was to nip off the troublesome St. Mihiel salient that so long had thrust its nose into the allied lines and had threatened France's greatest fortress, Verdun.

Clumsy looking but, agile, little whippet tanks appeared here and there and crawled out nosing for trouble. The artillery that had been pounding away since midnight at German wire, front trenches communications, batteries, and back areas, now laid down its protective barrage and the brown lines of infantry spread out in ragged formation.

By this time the story of how the rainbow came to lead the successful attacks of the division had become a cherished legend in the hearts of the doughboys. There was little promise of a rainbow to guide them that day for they had had no glimpse of the sun in more than two weeks of dreary, sloppy night marches. And the next day was to be Friday the 13th. The boys were depressed.

But the sign came. As the first defenses were taken and the lines moved forward, snipping their way through acres of tangled barbed-wire and running from cover to cover toward the sheer sides of Mont Sec, the sun broke through the clouds. Across the western horizon was flung in all its vivid colors the insignia of the fighting division. It was the good omen. The mountain was surrounded captured, and the march continued.

No one has yet satisfactorily explained the last appearance of the colors in the sky before the signing of the armistice. It was just prior to the final phase of the Meuse offensive. The Americans were waiting to burst across the Kriemhilde Stellung† "Kremhilde-Stellung" [sic] onto the plains before Sedan and to sever there the important lines of communication of the enemy. The whole division was at the time hiding in the rain-soaked, dripping Argonne forest, awaiting the word to advance to the forward positions.

One morning the sun appeared and drove every cloud from the sky. It was one of those warm, clear autumn days of early October. In the course of the morning a great aeroplane circled lazily over the woods which hid the division· It was apparently aimlessly patrolling the sky. In its wake it left a long, sinuous streamer of white smoke which scarcely moved from the spot where it was left, so motionless was the air. And on this smoke a band of rainbow hues appeared.

There is very little that escapes the notice of a great concentration of troops that have nothing to do but stay hidden. It was not long until someone had spied out the colors. Within a few minutes 28,000 pairs of eyes had beheld the sign and lusty throats began to shout. It was the prevalent opinion that the appearance of the colors foretold that the division was to be called upon at once to come to grips with the Boches.

Strangely enough all elements of the famous unit were in the lines within a week. Across the German stronghold, the Kremhilde-Stellung, the Yankees battled their way and won the great race to Sedan. The official American communique stated on November 9th: "The Rainbow Division and units of the First Division have captured that part of Sedan lying on the west side of the Meuse and the heights overlooking the city."

Once more the rainbow made its appearance to the division. This time it was not before a battle nor during a battle. It was on the afternoon of the 16th of December, 1918, as the Rainbow Division completed the last lap of its memorable march to the Rhine. To the strains of martial music the tired columns of doughboys rounded the last curve in the valley of the Ahr and came within sight of the Rhine. Just then a magnificent rainbow spanned the valley from the ruins of Drachenfels castle to the heights on the south side of the river. The war was won. The last objective had been reached and so appeared the emblem of success·

The average American will tell you that he is not superstitious. But you would have a mighty hard time convincing any doughboy of the Rainbow Division that the appearances of the emblem were mere coincidences. They were more than that he will tell you. They were omens of victory.

But it is not of the division, as such, with which this history deals. It must treat of but one phase of its activities. It is of the blood-red ray of the bow that we would speak, of the red cross of mercy as borne on the fields of France by the 117th Sanitary Train. It is our purpose to give an accurate account of the formation, training and activities of the train as a whole and of each unit of it, to serve not as a contribution to literature but as a lasting record of events which might otherwise become blurred or effaced from our book of memory as years pass.

PRIOR to late August, 1917, it is doubtful if the coming events had cascast much shadow on a certain little Long Island City, long sequestered from the rush and roar of modern American life. Hempstead Village, as it was politically called, had existed only in so far as it occupied a place on the map,—no less and little more. The residents seeming to be content to live and to let live, revered with true pride the rich blessings of Nature's choicest landscapes and the glory of time honored associations.

Indeed, the old colonial manner of life was preferred. It was like a trip into Yesterday, to stroll along the splendid avenues so magnificently shadowed by the stately elms and maples, or to drop into the historic little Episcopalian chapel, whose charter had been granted by Queen Anne. One could almost see the early days of America's history, with the Indian encampments, where crafty redskins bartered in wampum, hides, furs and feathers. Had Peter Stuyvesant, himself, stumped cholerically down a street there, no one would have been greatly surprised. Such was Hempstead Village in early August, 1917. It is very doubtful if many people other than New Yorkers had ever previously heard of the place, or of Camp Albert L. Mills, the official designation of the tract of land nearby, destined to become a great national mobilization point.

Then somebody suddenly realized that there was a war on hand. The newspapers had been conveying the intelligence for several months, but to all appearances Hempstead was but mildly interested in the coming of her guests. No sooner had a few O. D. men investigated the possibilities of the great camp site on the Hempstead Downs, however, than hundreds of National Guardsmen, the first elements of the 42nd Infantry Division, began to gather in the village and camp. Gradually, day by day, and hour by hour, was assembled the first complete, fully equipped National Guard Division in the nation's history.

The rough spots in the Nassau County roads soon became polished under the tramp of marching feet; the bray of the Army mule vied with the song of the meadow-lark, the crow, and the bugle, to sound the spirit of the crisp autumnal mornings; the heavy, ponderous combat wagons rumbled along the turnpikes,

the uniform of the U. S. Army made the color prespective to civilian eyes a veritable blur of olive-drab; the honk of the General's Klaxon and the bawl of the jitney drivers made the path of the pedestrian beset with peril. The theatres were jammed, the merchants waxed fat on spot cash sales, the traction system never knew such prosperity,—in short, Hempstead awoke from its Rip Van Winkle lethargy to find itself famous.

No microscope was necessary to analyze the colors present in the military spectrum. Infantry blue and artillery red, engineer cardinal and the maroon of the medical department were readily discernable in the riot of activity and color which prevailed on every hand. To form these maroon rays, eight companies had been assembled from the length and breadth of land. In the response to the President's call to arms, New Jersey's sons carried her spirit in the 165th; Tennessee's gift from the southland was the 166th; Oklahoma's offering from the plains of the Central West was the 167th, while Michigan contributed of her Wolverines, the 168th. These were the Ambulance companies. The no less essential Field Hospitals, bearing corresponding numbers, were composed of units from the white capitol of the Nation, from the wide prairies of Nebraska, from the timbered regions of distant Oregon, and from the shadow of Colorado's snow-covered peaks.

Toward this rendezvous on Long Island there had steamed forth into the rising sun long trains packed from end to end with boisterous youths and eager men with shining eyes and light hearts setting out on this great adventure. Thus were assembled the rays of the division's sanitary train, which, so far as localities were represented, might as well have been called Rainbow as might the larger units, the division.

Under the command of Major Herbert J.

Bryson, the first element of the division, the Washington, D. C. field

hospital company arrived in Camp

Mills. This was on the morning of August

20. In order that the sick and emergency cases in the units coming in

hourly, might be properly cared for, this company immediately pitched a 120-bed

field hospital at the main entrance near the Clinton Road. Owing to the pressing needs for more room, to

centralize the incoming regiments, the company was moved from its first position

to the permanent site near the ""back way to camp."" Here

under the orders of the Division

Surgeon, a 200-bed camp hospital was established, as well as a

surgical ward and operating room in the Nassau

County General Hospital at Mineola. The necessary fusion of theory and practice was well

under way by the time New Jersey Ambulance com-

8

pany

had arrived on August 25· Captain Peter P. Rafferty was commanding.

New Jersey at once made herself at home on

the turf, and had gained the divisional perspective of immediate service

overseas before Tennessee Ambulance company,

under Captain Percy A. Perkins, camped

alongside on September 1.

The following day

Oklahoma Ambulance company reached camp with

Captain H. G. LaRue in command. The 6th saw the completion of the Oregon Field Hospital's long transcontinental trip

and the westerners pitching tentage for Uncle Sam for the first time. Major James P. Graham was in command. Nebraska's company, directed by Major J. F. Spealman, rolled in and established

themselves with ease between Oregon and

D. C. on the

8th. Colorado appeared on the 12th, under Major E.

W. Lazelle, and the Michigan

Ambulancers brought up the companies to "all

present" when the organization marched into camp under Captain Robert J. Baskerville, on September 14th. The enlisted personnel of Headquarters had already been on the job since

late August.

Iodine and Gasoline

No commanding officer, whose sole duty was primarily to center in the work of the two sections had been provided for in this initial assemblage of the train. That is, as far as officialdom was concerned, the only connecting links between the ambulance and field hospital sections were the common purpose of caring for the sick, and proximity of situation. Captain Dunning S. Wilson was director of ambulance companies, and Major Charles O. Boswell director of field hospitals. Both sections were then responsible to Lt. Col. J. W. Grissinger, the division surgeon. Such fusion and dove-tailing as was necessary, was either done in the division surgeon's office, or in the offices of the respective sections.

Completing the quota of administrative officers of the camp were Lt. Jaspar W. Coghlan, who was known as assistant director of field hospitals and Lt. Harry A. Walhauser, who functioned in ambulance section headquarters, and was styled Adjutant. Making the K. P.'s, cooks, and tossers of the unsightly candy bag, toe the mark, and looking out for the general welfare and appearance of the camp was Major David S. Fairchild, sanitary inspector, with Captains Edouard DuBois and Thomas A. Buchanan and Lt. Morton P. Lane as assistants.

Despite the steady downpours of rain during those early September days, as soon as each unit was established an exhaustive series of exercises, drills, hikes, and lectures were taken up. Nothing that was at that time considered essential to the maximum efficiency of the trained medical men, was left untouched. The

The Saturday morning inspections were minute and thorough. Preparations for such usually began on Friday afternoons when every bit of debris was carefully interred or disposed of, the ground raked, scoured and swept and the equipment shined and cleaned until the vicinity ot the sanitary train gounds radiated like the rainbow itself. Three times a week all the tents were furled in order that the air might circulate freely and at least partly evaporate the numbing dampness of the enclosures

The sanitary methods in vogue around the train camp site were of the best. Any hour of the day or night a man might take a cold shower bath in the tapestried enclosures at the end of the respective streets. Rigid daily inspections were made to ensure† "insure" [sic] model spotless kitchens which were completely screened to keep out the flies. Running water was at hand just outside the door. All garbage was either buried or burned in makeshift incinerators nearby. Hence the general health of the sanitary train being constantly safeguarded, the number of men answering sick call was very small. A slight indisposition for a day or so after the injection of typhoid and paratyphoid prophylaxsis was not considered as illness.

In compliance with revised regulations, much of the old equipment formerly in use on the border was called in and new stuff was issued. The rusty old round canteen, the rubber poncho, the bolo or corps knife, old style haversack, leather belt, corps pouch and non-comm's medical case went into the discard. In their place the "U" roll came into favor along with hatchets, individual medical pouch belts, a canteen and cup shaped to fit the hip and various other "improvements." Alas, for the medical belt; its use has always mroe theoretical than practical. The bandages stuck together like glue and a week's sojourn in the tents so mildewed their medication that they soon became useless. It was next to impossible to remove them from their tight pockets. As for the hatchet, not a man breathes who had been dodging shells and the attending dangers of the battlefields who had not fumbled and cursed the unwieldly instrument in a thoroughly

soldier-like manner. Furthermore, the belt was a nuisance to the ambulance drivers who, in the cramped space at their disposal in the car, had practically no room in which to groan, much less to wear the things. The 117th Sanitary Train endured that girdle throughout the war and the armistice, and not a word of praise has yet been uttered in extenuation of the army medical belt.

Inroads on the numbers of the personnel, as deemed expedient in the modern scheme of war, early manifested themselves. Instead of the man being cemented to his unit as in previous crises, he was frequently automatically severed from his affiliations and sent to school, transferred to another company, or sent away on special duty.

On September 13, four non-commissioned officers and three men of the sanitary train who had been on detached service at the Medical Training School at Ft. Riley, Kansas, rejoined Nebraska. September 16, Lt. William P. Chalfant with four sergeants and five privates, first class, returned from Ft. Oglethorpe, where they had been attending a school of instruction since June.

Oklahoma lost 29 men on September 19, when in compliance with the tables of organization, her personnel was cut to a working force of 122 men. This was necessary, in as much as the company had just become motorized. The surplus men, representing the difference between a motor and an animal-drawn outfit, were distributed over the train as well as incorporated in the medical detachment of the 117th Engineers.

On October 1, when D. C. was relieved by a camp hospital unit, the company had hospitalized and treated 307 sick cases of various types, had performed 22 surgical operations with but two deaths in addition to innoculating and vaccinating against typhoid, paratyphoid and small-pox, practically the entire division.

The army mule was directly responslble for the war-time destinies of a considerable number of the men in the sanitary train, when on October 7 a special detail of seven men each from Nebraska, Oklahoma, Michigan and Colorado under the command of Lt. Joseph J. Nabhan of Oklahoma left for a southern port to superintend the general welfare and embarkation of the mules of the animal-drawn outfits. What was supposed to be a lark, and prior service overseas, developed into a prolonged and dismal sojourn in Newport News stables, pictorially rather than aromatically known as "Remount Station." Subsequently, however, all but three of the detail rejoined the train.

Outstanding among the many events during the train's stay at Camp Mills was the imposing review, September 23, before

Secretary of War Baker and Major General Mann. The train was the last of the divisional units to pass the reviewing stand on the Clinton Road. Despite the soldierly precision of movement and formation, the personnel was far from being in a sunny mood. They had previously stood in line for more than three hours on a very dusty road, during which time a stream of traffic had constantly passed, thereby making the men more like dusty millers in white than soldiers of the legion. But it was all in the game and that afternoon the men polished up anew and were toasting marshmallows by the genial firesides all over the island, and in New York.

The nature of much of the drilling made it more play than work. Leap frog, crack the whip, dashes and tug of war were entered into with as characteristic good nature and grim determinationn as though thesoilders† "soldier" [sic] were bucking the football line. Nor were the lectures at all hard to take, as they were replete with information on subjects of general interest. The men learned the ins and outs of the Articles of War and military courtesy, the difference between an acid and a corrosive poison, the why of a Ford ambulance part, how to stack a litter, the proper bearing of a soldier, when speech was to be silver and silence golden, and incidentally how to behave in a French billet. The men were led to believe that, although things would be somewhat different overseas, their quarters were to be choice, commodious and comfortable—a home away from home. The subject of cooties, bleak and frigid barns, and fragrant manure piles so dear to the heart of the French villagers, was avoided. It was taken for granted that experience and self-reliance would be the best teacher when the time came. If at times the meat in the lectures grew at all dry, the men never tired to watch the intrepid airmen overhead. To most of the personnel such exhibitions were something new, as one or two at a time were all that had been visible in the life lived before.

Many were the diversions in the ritual of the encampment as the weeks slipped by. Baseball claimed the attention of ardent players and a dozen fast, snappy games were played. An attempt to organize a league was made, but, owing to the lack of athletes in several units, and the short time at the train's disposal, only a few inter-company games were staged. An exhibition game between the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox players, at Garden City, was a treat for the train members to see.

A pay day arrived one Sunday, with its attendant shirt-tail parade around camp in the gloaming, to the martial music of questionable bugles enlivened by fire call, minus the blaze, and

the shooting up of the Robbers' Row of canteens. It was all as spectacularly staged as in the wild and wooly days of 1849. A storm second to none from the standpoint of fury didn't lessen the dampness of the island in the least, and the sanitary train will never forget that night of October 12 when the hurricane-like squall descended and made the campsite more like a Venetian city than dry land.

Ever a source of pleasure to the men of the train was the gracious hospitality of the Long Islanders who extended every courtesy within their power to make the soldiers feel at home. On Saturday afternoons and Sundays Hempstead, Garden City, Jamaica and Freeport became the meccas of attractions for a large percentage of the medical men. Such cordiality was better felt than expressed. It is more than probable that it was in the spacious reception parlors of the American Red Cross in Hempstead that many of the men partook of the last slice of honest to goodness cake ever tasted until their European experiences were lived and ended.

Sundays were quiet days in camp as the men were usually out to dinner, in quest of various and sundry amusements, or enjoying 24 hours of freedom in New York City. What had been but a tale or a descriptive article in the popular magazine or book a few months before became a sparkling reality as the soldiers saw the sights and the attractions of that great metropolis.

The experiences encountered during such pilgrimages will long loiter in the minds of the then unsophisticated westerners. Broadway and Coney Island, the Aquarium† "Aquariam" [sic] and the Zoo, the Woolworth and Wall Street, the subway and the "L," the Follies and the Hippodrome,—their features and disappointments were indeed well written on the pages of memory.

As West mixed with East, in mercenary ways and customs, many amusing incidents arose which, while binding the ties, nevertheless amused members of the sanitary train, greatly. One youthful medical soldier related that he was addressed by a middle-aged woman in a Hempstead confectionery store as follows:

Where are you from, young man?

Nebraska, ma'am.

There are lots of men here from Nebraska.

Yes, quite a few.

Nebraska must be a good sized town, what part of New York is it in

One soldier desiring to send a telegram to his folks, was somewhat surprised to be asked by the receiving clerk, What state

Camp Mills was ever and anon a sea of rumors. Nothing seemed too wild or increditable for the soldierly appetite. For a time the sugar-coated information perculated through the usual channels, that the Rainbow Division had been recently inspected by a "Lieut. Gen. Mogull" and found unfit for foreign servie. Furthermore, as a result of his findings, the sanitary train was to be sent south, probably to Cuba, to train for the winter. There was no mistaking the ultimate destination of the train, when on September 20, Lt. William P. Chalfant of New Jersey, sailed for New Jersey, sailed for France with the division's advance party.

Yet the men forgot that fact two days later when Germany and Austria staged one of their celebrated fake pleas for peace. The men accepted it at face value with a howl of joy which swept through the camp like a chip on a flood tide's crest. Next the Q. M. sergeants began to mark boxes of supplies "Arizona." The busybodies didn't stop to consider that such was a code word to fool Hun spies, but immediately began to enlarge the idea that the division was due for Border service. Visions of sand fleas, scorpions, rattlesnakes, heat, dust and abominations of that arid region didn't cheer the men's spirits in the least; for with the exception of Oregon, all the units had endured such a life the previous winter. Eventually, however, when the letters A. E. F. were added, foolishness took on a more somber tone. Belief and spread of these harmless rumors really served as a sort of patriotic camouflage to the facts in the case, in as much as the men were busy with foolishness when they might have been jabbering on dangerous facts. They obscured the positive order that the Rainbow was preparing as rapidly as possible for that mysterious country, "Somewhere in France."

Towards the middle of October, a certain definite belief that the division was about to move, took hold of the members of the train. A second physical examination was given with special emphasis directed towards sound hearts and lungs. A few physical defectives were eliminated from the personnel by this examination. Some of them had already registered for the selective draft and were subsequently inducted into the service again. William S. Shaw of Nebraska was later drafted and died of Spanish Influenza at Camp Meade. Fred Wynne of Tennessee was deemed unfit and discharged from the service but at the

close of the war was the Marine bugler on the U. S. S. George Washington.

Officer's trunks and barracks were crammed with extra clothing, shoes and little luxuries to cheer the residents overseas. Cots were stacked in the kitchen. The substantial long overcoats with their silken linings were exchanged for the short flimsy kind, about as warm as B. V. D.'s on a January night, a last strenuous inspection held, and the numbers of berths aboard a transport, doled out. When the men were finally confined to their company streets and not even pemitted to roam over to Robber's Row to put a dessert on dinner, something was undoubtedly in the air. Postcards to be mailed by the government, "Private A. Yank, at last arrived safely over there," were written and handed to the proper custodian. Some of these cards were actually delivered.

The soaring aeroplanes continued to fascinate spare moments, as one wondered how many would be drifting ahead over the numberless battlefields of war

During the midnight hours of October 17 and the morning of the 18th, the sanitary troops, unit by unit, slipped out of camp as inconspicuously as possible to entrain for overseas. What the next lap of the quest would have in store, not a soul felt like predicting. Enough was it, that a new brand of warfare hovered in the offing.

There were no bands playing as, with full equipment the personnel of the eight companies marched quietly out at the main entrance of Camp Mills, casting silent good-byes to those who watched them pass, and entrained at Garden City. Here patriotic workers of the Red Cross gave the men sandwiches dough-nuts, and cigarettes, accompanied by words of cheer.

Over at the docks in Hoboken, N. J., were seven ships, awaiting the arrival of a cargo new to them. They were all old vessels, having seen service before the war with the Hamburg-American Line. But as they had been Hun property, they had been interned by the United States in the early stages of the European war under articles of International Law. When hostilities opened between the United States and Germany, the ships were seized and converted into transports. Repairs were made and the necessary remodeling was done, but at that, they were in poor condition and their American crews were kept busy repairing one thing or another during the entire voyage. The names of these German freighters were changed for patriotic American names which were: " "Covington," "President Lincoln," "President Grant," "Mt. Vernon," "Pastores," "Tendores" and "De Kalb." More than 27,000 officers and men were to be divided among these seven transports. The escort consisted of the cruiser "Seattle" and two destroyers, making ten ships in all in the Rainbow fleet. Two of the transports, the "President Lincoln" and the "Covington," were submarined on later voyages while returning empty to America.

From Long Island City the ferry boat ride around Manhattan

It did not take long, however, for everyone to settle down to circumstances. After squeezing and maneuvering through the narrow passages between the three-tier canvas bunks, packs were disposed of by hanging them on water pipes and similar furnishings. True soldiers were the men of the sanitary train, so as soon as the doors of the mess halls were opened there was a grand rush. Appetites were keen for it had taken the entire day to get aboard, and breakfast had been a pre-daylight affair.

Not all of the train was assigned to the same transport. The "Covington," with Major General Mann, commander of the 42nd division, and his staff on board, claimed most, having the Division Surgeon's office, Field Hospital section Headquarters, and the D. C., Oregon and Colorado Field hospital companies. The "President Grant" carried among its passengers, Ambulance Section Headquarters, New Jersey, and Tennessee Ambulance companies, and the Nebraska Field hospital. Oklahoma was assigned to the "President Lincoln" while Michigan took a compartment on the "Pastores," formerly a United Fruit Company's freighter, which still oozed with the odors of South American bananas it had carried.

As fast as the transports were loaded they were towed into the channel, slowly making their way out past the Statue of Liberty to Sandy Hook. Many eyes were peering through port holes and hatchways and many minds were wondering "how long?" when the ships glided silently past the illuminated statue. Some even went without supper to take that parting glance and M. P.'s showed a soft spot in their hearts by allowing a few to stand on deck during these last precious minutes of fast gathering darkness over the homeland.

Everyone was tired and sleepy after the strain of the first day was over. No time was lost in making regulation beds on the narrow and short canvass bunks. The bunks were about the same on all the transports, being in tiers of three, with only a scant eighteen inches between them. The third story man had the advantage inasmuch as he was on top. Those having life belts

At three o'clock on the morning of October 19, anchors were weighed and the seven transports began their voyage towards France. Only a few were awakened by the clank of the anchor chains and the chugging of the engines. When the ship's electrician turned on the lights in the hold, announcing that the sun was up outside, and the familiar "Heave to, and lash 'em up" brought the sleepers to consciousness, the ships were steadily rolling, and those who rushed up the hatchway to the deck, saw nothing but the green water of the Atlantic and the rising sun. The first man on deck "braced" a hard looking sailor with the inevitable question:

Deck space was limited and the soldiers were plentiful. Each ship carried about two regiments. So each organization was allowed to go on deck at certain specified hours during the day, according to a schedule worked out by the ranking officers on the various ships. The average for an organization was two hours out of every twenty-four, but there were many who systematically worked out methods of staying up most of the time. Some even slept on the upper decks, perhaps feeling safer there than three flights down.

Ventilation in the hold was a difficult problem, as the ships were originally designed for freighters and were never meant to foster life below the first deck down, where the crew slept. The regular ventilating systems of the ships were ample for the first deck with its lounging rooms, mess halls and seamen's quarters, but the compartments below the water line were airtight and dark, and those next to the engine rooms were hot as ovens. Auxiliary canvas ventilators were rigged up but even then it was stuffy and hot and many of the men lay on their bunks during the long evenings and nights, in the uniforms issued by Mother Nature. Owing to the bad air and crowded conditions, a ban on smoking in the steerage compartments at any time was put on after the first night.

Days and nights passed very slowly, especially the night, for lights were turned out at the first appearance of twilight and

Peculiar ailments in the regions of the digestive organs began to appear among the train members on the second day at sea. A few took refuge on their bunks and in one or two cases, scarcely ever left them. The odor of "slum" and other foods in the mess halls made those places the chief scenes of disorder. The sufferers were a sorry lot and to some a torpedo from a German sub would have been welcomed. All in all, they became firm believers that Columbus was a brave man and shook hands with themselves for not enlisting in the navy. Most of the cases obtained their sealegs and recovered rapidly while a few were unable to appreciate life throughout the entire voyage.

A good example of Hun efficiency came to light the third day out, when the "President Grant" developed boiler trouble and began to lag behind. Even though all boats had been pronounced seaworthy after their trial trip, some clever German engineer had removed a minor part, calculated to disable the ship in midocean. On the evening of the fourth day, it was finally decided that the "Grant" was unable to run the danger zone, so with a good-bye toot of her whistle, she turned her prow towards New York, taking Ambulance section Headquarters, New Jersey, Tennessee and Nebraska with her.

It was a great disappointment to these members of the sanitary train, for visions of Europe and the battle fields were temporarily shattered and the train was scattered for the first time since its organization. The "Grant" docked at Hoboken on the afternoon of October 27, and the troops were sent to neighboring camps to await their second attempt to cross.

"Abandon ship" drills were inaugurated early in the trip. Orders required each man to carry a blanket and a canteen full of water besides wearing his overcoat and life preserver, when attending these drills. Instructions were issued in detail about what to do if the ship was actually abandoned. Everyone was assigned to either a life boat or a raft. Rafts were plentiful and were set apart for the use of enlisted men. Each company was assigned a spot on the gun deck, and whenever the alarm sounded, every man went to his company's rendezvous promptly, taking pains neither to hurry nor to loiter on his way. Nobody ever knew when the alarm sounded whether it was genuine or only a

At first life belts were only to be kept handy, but after the danger zone was entered they had to be worn or carried at all times. "Abandon ship" drills came any hour of the day or night when least expected, and sometimes twice or three times a day. Drills were not held while the convoy was running the danger zone. In the moments of relaxation after the drills conversation always ran high. One could hear on all sides remarks about submarines, torpedoes, life belts, blankets, and various statements as to what should be done in case the ship was torpedoed. Everybody wanted a boat instead of a raft, for rafts were flimsy looking affairs and their occupants would be waist deep in cold water. General opinion changed, however, for on an occasion when the boats were lowered, the bottom fell out of one, the two sailors in charge being saved by their swimming ability. The incident was one more example of the subtle deviltry of the Hun. The boat had been put together with nothing but glue. Following the event all of the boats and rafts were subjected to a rigid inspection. The drills came to naught and the boats and rafts were never used ; thanks to the good work of the navy.

The cruiser and two destroyers were not the only protection the convoy had against the stealthy submarine. Each transport was armed with one or more six-inch guns and also with a few of smaller calibre. The guns were manned by experienced crews taken from battleships. Even experienced as they were, target practice was necessary in order that the gunners might be able to deal properly with a sub if one made an appearance. A moving target, towed behind one of the ships, and resembling a periscope, was used. The transports took their turns firing and after these performances the men's fears somewhat subsided. Many direct hits were scored and there were few shots that went wild. Keeping the guns trained on the target in a rolling sea as those gunners did, was a wonderful feat in itself. The practice was a rare sight to the soldiers for it gave them an idea of war on the sea, especially when a cruiser fired a broadside. Of the transports, the "De Kalb" was the most heavily armed, carrying in all twenty-six guns.

Life on the ocean was not without work or amusement. Washrooms, troop compartments and mess halls had to be cleaned every day by details selected from the personnel of the various organizations. K. P.'s were not forgotten and a few enjoyed a sojourn in the kitchens with the navy cooks. The navy medical personnel on one or two of the transports was insufficient to care for both sailors and soldiers, so the train furnished some of its more experienced wielders of the iodine swab to assist in the sick bay. This was looked upon, more or less, as a "soft job" for the red cross arm band permitted them to go to any part of the vessel at any time. It was also a known fact that the sick bay was the only place on board where a real thirst-quenching drink of water could be obtained.

Time was heavy on the soldier's hands and he was thrown almost entirely on his own resources for amusement. Whenever the weather permitted, band concerts were held on the main deck, but these only occupied a short hour of the day. Impromptu programs were sometimes given in the evenings. Every available book, magazine and paper was carefully read by the pale blue light of the hold. Those who were not inclined, or were not lucky enough to have something to read, played cards, shot craps, or discussed the prospects held in store by the war. Some of the more energetic, burled themselves in French grammars and hand books, so that they would be able to "parlez vous" when the voyage was finally ended and they were on solid ground again. Curiosity led many of the bolder characters to explore the ship, visiting the many compartments, store rooms and even gaining entrance to the engine rooms. When nothing else could be done, the men lay on their bunks and slept.

The two hours of breathing time on deck were taken up by attempts to run the canteen line—a feat rarely accomplished—dodging the spray, making up for lost smokes, and above all, searching the waves as far as the eye could see for submarines or other vessels. Whenever a strange ship made an appearance, the destroyers immediately investigated, and once when all guns were leveled on a mysterious boat, everyone was on edge for "something doin'" until the competent chasers signaled that all was well. Especially after the danger zone was entered were all eyes strained for the sight of a periscope or the white wake of an on-coming torpedo, but never were the searching glances rewarded.

Day after day went by with no signs of ever getting anywhere. All there was to be seen was "water, water everywhere." Everyone† "Every one" [sic] was getting downhearted. Was land never going to

be sighted? Rumor had it that a large escort was to relieve the original one which the men deemed inadequate. Every day someone heard that the convoy was to join the fleet that night. Every morning coming on deck, all would look for the missing destroyers. Fear began to spread that the Rainbow had been forgotten and would have to face the dangers with very little protection. The suddenly one morning, after all hope had been cast overboard, the fleet was surrounded by eleven mysterious and grotesquely painted crafts. They darted in and out, here and there, seemingly leaving no spot uncovered in their nervous plungings.

Here was a new diversion, for the ocean-weary soldiers, watching the pitching, rolling, wildly daubed destroyers patrolling the sea. This was the first time the men ever saw camouflage. Their arrival was soon accounted for when a "sailor told a soldier" that during the previous night, the fleet had almost run into a submarine nest, only being warned in time to change its course, while the two destroyers gave chase.

The feeling that land was not far away began to take hold of the troops and visions of Sunny France occupied their imagination. Obliging sailors put out the information that the fleet was in the Bay† "bay" [sic] of Biscay and would soon be in sight of land. Much wreckage, a life boat, several rafts and boxes were seen afloat. Seagoing vessels could be sighted in the distance, gulls swarmed about the transports and a general cleaning and inspection of troops' quarters took place. Still the once-clean but now filthy life belts had to be worn at all times for it was said that this was the most dangerous water of all that the fleet had passed over.

On the morning of October 31, word was passed below that land was in sight. In a few minutes the decks were crowded and heads were protruding from every port hole, drinking in the welcome sight of Belle Isle. Everyone drew in a deep sigh of relief as the fleet passed through the submarine nets between the mainland of France and Belle Isle. Life belts were thrown aside, and one by one the transports entered the channel of the Loire River† "river" [sic]. Thousands of small fishing boats dotted the water on all sides. The channel was shallow and all the transports were heavily loaded, so very little headway was made during the day, even with French pilots on board. This only aggravated the already impatient men who were anxious to bid farewell to transports and set foot on good hard ground once more.

At 3 o'clock on the morning of November 1, 1917, the six transports docked in a French seaport with the Rainbow Division. Thus after an uneventful voyage of fourteen days the personnel of the sanitary train waked to find themselves harbored safely in St. Nazaire.

The entire day was spent on the boats, and from the decks the men had their first glimpse of the Boche,—a harmless, domesticated type, commonly known P.G.'s. They were doing longshore work on the dock, unloading supplies belonging to the U. S. A., and every box they handled was bringing the German defeat just so much closer. In charge of the entire group of about fifty, was one French guard, and he was much more interested in watching the masses of O. D. clad soldiers over the rails of the transports, than in keeping check on his prisoners.

This guard was the first man seen wearing the horizon blue of the French, so familiar to every member of the A. E. F. To the men on the boats he was representative of the millions of brave Frenchmen, who had fought, and were still fighting, for Right against a foe as merciless and cunning as a famished wolf pack. He was one of the men whom they had crossed the ocean to help; and they were glad they had come.

In another place on the dock was a group of American negroes in the overall uniform of the stevedores. They seemed to be enjoying life just as much as if they had been on some Dixie wharf, handling cotton bales instead of unloading munitions of war in France.

Here and there were stern looking American Marines doing general guard duty on the dock. "Hard boiled" was the word the boys employed in describing them.

As soon as the civilian population of the city became aware that a new convoy of Americans had arrived, they flocked to the water front. These were not the first Yanks they had seen, but the appearance of these boats, swarming with strong, sturdy, young soldiers from a far-off land, arriving safely from a sea infested with German U-boats, had not ceased to thrill and interest them. The men on the boats were interested in the civilians, too, because they wanted to see and know more about the people whom they had come so far to help. The most noticeable thing about the crowd was the almost total absence of able-bodied men. The few who were there were in uniform. The remainder of the crowd consisted of old men, women and children. The women were all dressed in black, and many of the men wore mourning bands on their arms.

The water around the transports was crowded with small boats, loaded with children, who begged souvenirs, and offered chocolate and apples for sale, and many a service hat was lowered by means of a cord or rope, filled with many apples or as much chocolate as the money in the hat would buy, and hauled back up into the porthole.

When evening came the impressions of France in the minds of the soldiers were strange and varied, but as they lay down on their canvass bunks that night, every man was glad that he was there and proud to think that he had volunteered to come.

On the morning of the 2nd of November, Michigan debarked from their boat and, leaving a detail behind to take care of the company equipment as it was unloaded, they marched through the city and out to what was known as Camp No. 1, their first home in France. This camp was composed of French wooden barracks and furnished shelter for approximately 1500 men. It was used for housing men who came off the boats until transportation could be obtained to carry them inland. Here the men had a chance to get rid of their sea legs, to bathe the salt crust off their bodies, to wash their clothes, to replenish their supply of tobacco and cigarettes and learn to count in francs and centimes.

The same day, a detail was chosen to proceed inland and arrange for billets in the towns where the train was to make its first home in France. One non-commissioned officer from each company formed this advance party, in charge of Captain Robert C. Cook of Colorado.

The other companies, Oklahoma, D. C., Oregon and Colorado were taken off the boat at different times during the day, marched through the city to Ocean Boulevard and there given a few minutes' freedom for the purpose of stretching and exercising the legs and bodies that had necessarily been idle for the last fifteen days. The boulevard was deep with sloppy mud and the boys were wearing light barracks shoes, but they enjoyed it just as if they had been on the finest lawn in the world. They were on land again and they knew that no submarine could nose up under them and blow them all into "kingdom come." On the return trip to the boat, the companies marched through the principal streets of the city, crooked, narrow streets to be sure, but principal streets just the same.

The city of St. Nazaire is situated at the mouth of the Loire River† "river" [sic], and until within the last 75 years was a small village with a harbor that would accommodate only fishing vessels and boats engaged in trade along the coast. At this time it was found that the ports of Brest and Bordeaux were not large enough to handle all the shipping that came to France from the Atlantic. To remedy this the French government decided to make improvements at the mouth of the Loire, so all but the largest type of ocean craft could come into the harbor and be docked. During the time these improvements were being made and after their completion, the population was greatly increased and the city itself was built up. Properly speaking it is not one of the oldest cities of France, but to these men from America it seemed to be the very superlative of all things old.

The first evening all the men were held on boats, but on the following evening a certain percent† "per cent." [sic] of each company was granted shore leave and these men explored the city in their way. They found a great difference from the things that they were used to at home. The shops were all small, and, with the exception of those handling military accouterments, very little display was made. It was almost impossible to buy anything to eat except roasted chestnuts. There were a few places where cheese sandwiches could be obtained, but they were more expensive than chicken dinners in the States, and as most of the men had spent most of their entire month's pay on their last trip to New York, they invested in very few sandwiches. The French people were all anxious to talk to the Americans and it was then the men received their first lesson in French. They learned that "bon soir" meant "good evening" ; that "au revoir" meant "goodbye" , "bon chance" meant "good luck" . If a Frenchman came up to a bunch of the boys and jabbered something at them that

During the next four days, short exercises, marches† "marchs" [sic] and shore leaves were the things of most interest. Details were kept on the docks to take care of equipment and barrack bags as they were unloaded from the boat, and to handle the four days' rations that were issued to each company.

On the morning of the 6th of November, Michigan left Camp No. 1, and boarded a train composed of third-class coaches. Eight men were crowded into each compartment along with their personal equipment and two days' travel rations. This left them scarcely any place to sit down and of course lying down was out of the question. In the evening all the other companies left the boat and splashed through mud to the railroad yards, in the drizzling rain that had kept up, intermittantly, ever since their arrival in port. A careful scrutiny of the yards showed nothing but box cars and everyone thought that they would have to stand around in the rain until some passenger coaches were pulled in. They were soon disillusioned, however, for they found that they were to take the "8-40" train, so called because each of the box cars was marked "Cheveaux 8, Hommes 40" . To get forty men into one of these dinky cars, along with their equipment and travel rations, meant that they must stand. There was no room to sit or lie down. Evidently transportation was scarce. They crowded in, piled their corned willy and hard tack in the middle of the floor, and made the best of it.

The train started at dark and moved slowly with frequent stops throughout the night. At one halt, a so-called French coffee station, the men were each given a cup full of villainous, black concoction closely resembling diluted furniture polish. Its only redeeming feature was the fact that it was scalding hot and that made it welcome to the men, who were wet and cold. There was no heat in the cars, and the men, wet from the late march through the rain, became chilled to the very marrow. For the first time since entering the service they were thoroughly disgusted.

When morning came, the sun showed itself for the first time since land was sighted and everyone after exercising on the station platform during the numerous stops, began to take a new interest in life.

After the morning repast of cold canned tomatoes and hard tack, the discomforts of the night were forgotten and the scenery occupied everyone's attention. On every hand there was beautiful level valleys divided into a patchwork of plots, and long sloping hills, terraced and cultivated to the very top. There were no scattered farm houses as in America, but every few kilometers there was a small village of stone houses, red tiled roofs, crooked streets, and small gardens, nestling against the hill. The most prominent point in each village was its high-spired church.

The second night on the train was not as bad as the first. The men had thoroughly dried their clothes during the day, and some had opened their packs and had taken out the blankets as extra protection from the cold.

The iron rations were eaten with relish, for the men were not yet fed up on it. Twice each day the French issued out their weird† "wierd" [sic] potion, under the name of coffee.

The scenery the second day was virtually unchanged, except that the country was a bit rougher and did not seem so well cultivated as that nearer the coast. The villages, houses, and churches were all the same, the population apparently the same as at St. Nazaire. A few young men in uniform, and all the rest old men, women and children.

after noon on November 8, the train arrived at Vaucouleurs-Sur-Muese, and Oklahoma unloaded. Michigan, which had arrived at four o'clock the same morning, had already discovered that "billets" meant barn lofts with leaky roofs, dark wind-swept sheds and cold bare rooms in houses, instead of the comfortable rooms with feather beds that had been pictured to the boys. Both companies, however, soon found that they had no time to spend in their billets except while sleeping. Before leaving the train at Vaucouleurs the men heard their first sounds of war the faint rumble of artillery fire on the front between Toul and Verdun. Although the sound was indistinct the men felt that they were at last nearing the object of their search. They had traveled many thousands of miles and many days and at last they had drawn close to the war.

After two hours' delay the train moved on, and well after dark it arrived at Mauvages, in the Department of Meuse. The men who hobbled off the train and, in the rain, unloaded their

Here the three hospital companies, D. C., Oregon, Colorado, had received their introduction to lofts and barns as sleeping apartments. The strange places made no difference to the boys that night, they were all so tired that any place where they could lie down and stretch out was welcome as the best of beds.

In the chill of the next morning, though, the red-roofed houses looked dingy and dirty at close range, the crooked streets were sloppy, muddy, and lined with piles of barnyard manure, reeking and steaming. The people showed evidence of a soap famine. Even the sky was a dirty gray and promised more rain. The first duty was to clean out the billets and try to make them habitable. Kitchen sites were located and wood was "procured from the French. The men bathed or washed clothes in French style, in cold water, with soap, brushes and wooden paddles. These last articles were borrowed from French women washing nearby.

There followed street cleaning. The populace did not understand why streets should be cleaned, and very few of the men could speak French enough to explain it. But they cleaned them just the same, and after a few days of hard labor the Americans gave to the old town a much more respectable and more sanitary appearance.

On the 11th of November, Colorado opened the first hospital operated by the 117th Sanitary Train in France. The building was a neglected, moldy old chateau when they started to clean it up. Hot water and vigorous scrubbing made it serviceable at the end of two days' hard labor. An epidemic of mumps arose among the 117th Engineers who were in the same town as the hospital section. With mumps and the ordinary sick, there were 74 patients in the hospital when Oregon relieved Colorado on November 15th. Colorado, after being relieved moved at once to Chalaines, a small village just across the river from Vaucouleurs. They took over a hospital from the French—Camp Hospital No. 16—a large chateau and two wards nearby, one of which was an operating ward. This hospital handled the sick from the division, many mumps, and the usual influenza and throat troubles. A detachment of medical officers and female nurses from Base Hospital No. 36 were attached to Colorado while it was operating at Chalaines.

On the second of December, Oregon closed its hospital at Mauvages and began a series of hikes and drills, for the purpose of toughening the men for what was to come later. While operating this hospital, they had cared for a total of 84 patients, a very difficult task, owing to the lack of medical supplies and hospital equipment.

On December 5th D. C. left Mauvages and hiked to Burey-en-Vaux, a little village of about a dozen barn-like buildings grouped around an old chateau. In this chateau it opened Camp Hospital No. 17 and in a few days it received 25 patients.

During the time that the hospitals were getting established, Oklahoma and Michigan were busy in Vaucouleurs, but not in handling litters. Upon their arrival there a few days of repose were allowed, and during that time nearly all the men visited the ruins of an old castle, which was situated on the hill back of the town. The castle, built in the early part of the 15th century, is a heap of ruins, excepting its great stone archway, and an underground chapel. It was through this arch, called "Porte de France," that Jeanne d' Arc rode when she came to the little underground chapel to pray for Divine aid and guidance in her mission of leading France to victory.

The village of Vaucouleurs had two industries, a statute factory and a munitions plant. The former was the larger, employing in peace times several hundred men, women and girls. The munitions plant employed mostly women and girls, working on hand grenades. The streets were paved during Caesar's† "Ceasar's" [sic] time, according to legend, but were still intact. The paving was not visible on the arrival of the troops, but after the details for the ambulance companies had labored for a few weeks, washing and sweeping in accordance with the custom of the Medical Department, they showed like new.

After about a week of sightseeing, bathing, washing clothes, and studying French, the entire personnel of Oklahoma and Michigan, with the exception of the street cleaning detail, were put to work handling supplies on the quay, where a large American Q. M. depot was being established. They unloaded and set up ambulances, escort and combat wagons and rolling kitchens. They carried bacon boxes, until they could grunt like pigs. They shoveled coal, corded wood, juggled oats and baled hay and in fact were temporarily the stevedore section for the entire Rainbow Division.

At about this time three, four-mule teams and wagons were issued to each of the three field hospitals and to Michigan. They were sad looking mules, just off the boat after a voyage of a

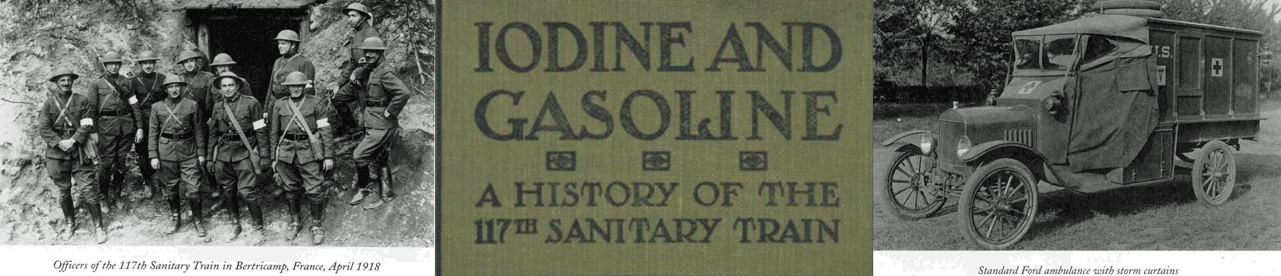

On November 16, Captain Frederick W. McAfee of Michigan, with a detail of 55 men, traveled by train to Paris and spent 12 hours in the forbidden city. In the evening they were taken to a big farm near Meaux, the farthest point reached by the Boche in 1914. The next day they started for Vaucouleurs with 36 Ford ambulances under their own power, arriving two days later. Twenty-four of these ambulances were turned over to Oklahoma, six to Colorado, and the remainder scattered among the regiments. These ambulances were used for collecting patients from the regimental infirmaries and for evacuating patients from Camp Hospitals 16 and 17, to Base Hospital 36 at Vittel, and No. 18 at Bazois.

On December 11 both Colorado and D. C. evacuated their and that evening the barrack bags of all five companies were packed up and sent away. The rumors that had been circulating for a week were coming true. The train was going to move. Every man felt as if he were an old campaigner by this time and wanted to go towards the front.

Instead of toward, the hike lead away from the front. On the morning of the 12th, Colorado and Michigan with their kitchens and equipment on wagons, and their men marching, started from Vaucouleurs in the rear of the supply train column, and behind them came Oklahoma. At Burey-en-Vaux, D. C. was lined up and joined the column. Fortunately the roads were dry and the marching was comparatively easy, as marching with a full pack goes. At noon a halt was made at Maxy-sur-Vaise and iron rations were munched. After an hour the column moved on again. The afternoon was not so easy as the morning. The sun seemed boiling hot. Pack straps began to chafe tired shoulders, blistered feet became more painful and the attending ambulances soon became loaded. At dark the column stopped at Maxey-sur-Meuse and the men were billeted in barns and lofts. Oregon and the hospital headquarters arrived ahead of the main column, under the guidance of a company of M. P.'s who had been lost on the road three times during the day. After supper everybody literally "hit the hay" , and slept soundly until first call roused them. The men stretched their aching bodies, dressed and fell in for reveille. By 8:30 o'clock, the column was on the move again.

Soon after setting out the column passed through the ancient and historic Domremy, the birthplace and girlhood home of d'Arc. The house where she was born still stands and the

Before noon the column had passed through the old city of Neufchateau and an hour later it stopped at the roadside for lunch. All afternoon they marched, and in the evening stopped at Goncourt. Here the men were quartered in Adrian barracks, and spent the night on bare wooden bunks.

In the morning packs were rolled and the grounds were policed. The wagons had been sent ahead with orders to halt after fifteen miles'† "miles" [sic] journey and prepare hot dinner for the men marching. However, the regular army officer in charge of the night's resting place, after making microscopic† "miscroscopic" [sic] inspection, decided that the National Guard men had not properly cleaned the camp. The companies that had already marched out into the highway were called back. Packs were unslung and policing started again. There were about 1000 men in the group and the grounds were again gone over thoroughly, but still it did not please the chloric officer, and he ordered it all done a third time. "Pick up everything the size of a match stick or larger, in the whole valley," was the order passed down by the sanitary sergeants.

Never did Germans hate British as the men of that column hated that picayunishly exacting officer, but they picked up match sticks while they were hating. An hour before noon Major General Mann, the divisional commander, drove up in his car and the officer responsible for detaining the column was brought before him. Immediately after the General's car rolled away the column moved out. They had been held for four hours on a trivial pretext.

This day's march was the hardest of the entire trip. The men were chilled and miserable, for it had been raining nearly all the time that they had been waiting. A company of doughboys without packs headed the column and set a pace uphill a little slower than double time. After reaching the top of this three-kilometer hill, the troops passed a section of trenches and barbwire entanglements, one of the training sectors of the French. The French troops drilling there stuck their heads up and gazed, in wonderment and surprise, at the Americans as they raced by as if the whole German army was close upon their heels.

Dinner time came but no dinner. The kitchens had gone ahead according to their original orders. Before St. Blin was reached

The train was quartered in draughty, thin-boarded Adrian barracks furnished with wooden bunks that were new and clean. No bedding was furnished by the army, but the boys were not long in finding a Frenchman who was willing to sell straw at the rate of two francs per tick full, so they were able to make themselves fairly comfortable after the first bike in France. The heating arrangements was a small stove at one end of the long building, but it was so small and wood so scarce that it was of virtually no use. The only way to keep warm during the winter weather at St. Blin was to go to bed.

On the 15th of December, the first heavy snow fell and after it came rain and sleet, leaving the ground and roads covered with a solid sheet of ice. The mules were all smooth-shod and until some of them could be reshod, it was almost impossible to draw rations for the companies.

In spite of these weather conditions, a five-mile hike with full pack was scheduled for each day, "in order to get the men into condition" .

While at St. Blin, Major Marion B. McMillan was assigned as director of the hospital section, succeeding Major Charles O. Boswell, who was relieved while at Mauvages. On Christmas eve at Lafauche† "La Fouche" [sic], where the Division Surgeon's office was located, Major David S. Fairchild was made a Lieutenant-Colonel.

On the day before Christmas a detachment of twenty men left at Chalaines by Colorado to care for patients who could not be moved, rejoined their company. On Christmas Eve† "eve" [sic], a small consignment of mail and packages was received, bringing a taste of Christmas joy to the hearts of these men who were spending their first winter in France. Christmas dinner included turkey, with as many of the of the trimmings as could be obtained. The troops showed their spirit by decorating their barracks with holly and mistlletoe gathered from the nearby hills. For the first time since their arrival in France the men were permitted to send cablegrams to the folks, thereby† "therby" [sic] leaving a few words of cheer in their vacant places by the old home fireplace.

Thus, despite the many unpleasant little initiations to bizarre tasks in the constant rains of Sunny France, despite the irksome "ragging" of the officious bosses, forgetting cheerless billets, and other hardship, the personnel of the 117th Sanitary Train passed a pleasant Christmas. They had become soldiers.

As usual during a move, the rain came down in torrents and everyone was drenched to the skin. but the boys made the best of it and relieved their feelings by singing the then popular song, "Where Do We Go From Here." As to this they had not long to wonder, however, for on October 31, ambulance section headquarters, New Jersey and Nebraska, loaded on a ferry which took them to Weehauken, N. J., where they entrained for Dumont. They arrived late the same afternoon and marched to Camp Merritt, N. J. Tennessee remained at Fort Totten under quarantine during the entire time until again embarking for France.

Nearly everyone in the organizations stationed at Camp Merritt, received passes to visit New York City, and the men from New Jersey visited their homes. It was during the stay here that Captain Wilson, director of the ambulance section, was commissioned major.

On November 12, Private Jacques D. Wimpfheimer† "Wimpheimer" [sic] was sent to the hospital in Englewood, New Jersey. A few days later he was removed to a hospital in Hoboken and on January 23, 1918, he died of pneumonia. He was the son of the Jersey Company's financial support and guardian, Charles A. Wimpfheimer† "Wimpheimer" [sic], prominent New York merchant.

On the morning of November 14, 1917, the four organizations received orders to embark a second time for France. This was accomplished the same morning. Ambulance section headquarters, New Jersey and Tennessee, embarked on the R. M. S. "Aurania" at pier 56, New York City, and Nebraska embarked on the White Star liner "Celtic" at pier 60, New York City. Both ships put out to sea at about 3:30 the same afternoon.

Life on board these English ships was more pleasant than it had been on the "Grant." The men had better living quarters and were not so crowded. There were canteens aboard these

The "Aurania" was a better ship for comfort but the kitchen was English and it is needless to say that "Chaze and Tay, twice a day" was the diet during the voyage. The voyagers touched at Halifax, Nova Scotia, November 16, at 4 o'clock P. M. While here an opportunity was given all men to write home, the letters being gathered, censored and sent ashore. After waiting there forty-eight hours they joined the other ships of the convoy, nine in all, and put out to sea. A British cruiser in the harbor paid the Americans a tribute by allowing her band to play the "Star Spangled Banner" and the crew stood at attention as the convoy steamed past.

In spite of the bad weather the different organizations proceeded through a regular schedule of physical exercises and lifeboat drill. The gunners on the "Celtic" had target practice from time to time. The concerts which were rendered by the 168th Infantry band on the "Aurania," the first few days of the trip, had to be discontinued on entering the war zone.

Due to the efforts of two Canadian Y. M. C. A. secretaries, who were crossing, to join their troops at the front, several first class entertainments were produced during the voyage. Among the best was a minstrel show given by a few of the boys from New Jersey and a benefit performance for the Orphans of British Seamen, in which members of the company took part.

The English sailors could not understand many traits of American soldiers, above all, how they could play poker and joke with such care-free actions when danger was all around.

When on November 25, the men were ordered to sleep with their clothes and life belts on, it was easy to guess that the convoy had reached the danger zone. November 28 proved to be the most exciting day of the journey, when something very similar to a periscope made its appearance a short distance away and passed within a hundred yards of the "Aurania." The Sharpshooters who had been posted at different points on the ship some time before, opened fire with rifles. The "Celtic" immediately spun around, so as to present as small a target as possible, opening fire with her stern guns. Two destroyers were immediately on the scene firing perhaps a dozen shots in rapid succession. The alleged periscope disappeared, and the fleet changed its course, putting into Belfast harbor about dark. While the troop ships lay in the harbor, the accompanying destroyers scoured the Irish coast for submarines and mines.

Morning brought the rumor of a naval engagement and a

It was just a coincidence that Private James Brownlee of the New Jersey company could stand on deck at this point and see the chimney of his mother's home in Belfast, which he had left as a boy, ten years before. But being in the army and shore leaves not being granted, he was near and yet far. Taking a furlough from his post on the Rhine fifteen months later, Brownlee was at last permitted to visit his mother.

The fleet lay in the harbor on Thanksgiving day, while the stomachs of the men were being insulted with Australian rabbit, refrigerated for an uncertain number of years and finally cooked with the hair on. The "Aurania" had been transporting Canadian troops to France for three years. Maybe the management did not remember that the American Thanksgiving was a feast day, and that to starve Americans on that festive occasion was injury to the extreme.

Leaving two freighters, one of which was disabled, the remaining seven ships left the harbor of Belfast at 2:30 o'clock on the afternoon of Thanksgiving, convoyed by nine destroyers. They proceeded at top speed under cover of darkneas to Liverpool, England, casting anchor at one o'clock A. M., December 1, 1917. It was indeed a happy crowd who marched down the gang plank and immediately to the depot of the London and Northwestern railway.